As the food culture in America has grown, exotic foods have made their way into mainstream diets. Quinoa, agave, and edible flowers are now found in most grocery stores as ordinary meals become more diverse.

As the food culture in America has grown, exotic foods have made their way into mainstream diets. Quinoa, agave, and edible flowers are now found in most grocery stores as ordinary meals become more diverse.

It was only a matter of time before someone raised the ante to bug cuisine. I blame The Lion King.

On May 13, the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization published a news report that advocates for entomophagy, or the practice of eating insects. Predictably, the concept confused many people, and disgusted even more. But strong evidence supports this recommendation. U.N. officials predict that increased entomophagy will promote human health, create jobs, and improve the environment. However, will this reasoning be enough to convince the Western world to trade steak for crickets?

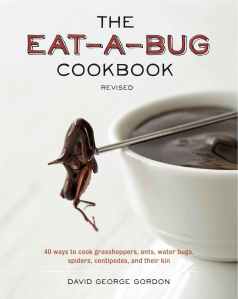

David George Gordon's Eat-a-Bug Cookbook explains that our cultural disdain for eating insects stems from the Western history unfairly demonizing insect "pests" that hindered technological advances. Gordon has maintained for years that entomophagy is actually a "widespread, nutritionally beneficial, and unquestionably wholesome practice" that over 80% of the world's population engages in. Though it may seem repulsive to us, other cultures regularly feast on insects.

Of course, most people don't eat these creatures plain. They savor the insects in flavorful dishes like savory soups, stir fries, and baked goods. Gordon, the "Bug Chef," shows this with his book's tasty recipes which include Scorpion Scaloppine and Orthontera Orzo.

Gordon's cookbook also explores the entomophagy's history and anthropology. His research, along with other sources, shows that eating bugs is an ancient, time-honored practice. National Geographic relates that the Ancient Greeks and Romans harvested beetle larvae and cicadas, and many Latin Americans still savor traditional dishes that include tarantulas, ants, and worms. The article also describes the consumption of crickets in India, flies in Japan, and grubs in New Guinea -- diverse entomophical practices in our diverse world.

Also, John the Baptist survived the desert on honey and locusts. Just saying.

With such popularity, these bugs must not taste all that bad. Of course, different bugs have different favors. Most people describe larvae as similar to mushrooms or escargot. Spiders and scorpions apparently taste like shellfish. Other bugs are citrusy, although most are considered nutty.

Besides the taste of this tradition, the nutritional benefits of entomophagy are well known. Time reports that bugs are natural source of protein and fiber, and can easily form a healthy addition to our diets: "insects scoring high in nutritional content include silkworm pupae reaches, bamboo caterpillars, wasps (yes, wasps), Bombay locusts and scarab beetles." Their nutritional density ranks higher than most meats.

Farming edible insects also provides a global outlet for sustainable farming, which would provide many jobs in an eco-friendly manner. The Wall Street Journal claims that "Raising insects for food would avoid many of the problems associated with livestock." Farming insects is much more efficient and less destructive than cattle, for instance, using less land, water, and waste.

So with all of these benefits against a rich background, will people give crickets and worms a try? After all, if was good enough for Simba, it should be worth a taste test.

What do you think?

You can find more about the culture and practice of entomophagy with Gordon's upcoming revised cookbook.

More Resources:

No comments:

Post a Comment